By Claire Kaplan, Advocacy Intern

If you drive on highways (or walk and bike underneath their overpasses) you already know that maintaining our roads is critically important. But infrastructure means more than roads, highways and bridges. It means schools, hospitals, water and even the internet. Infrastructure is one of the most essential services a government can provide for its people, and failure can mean catastrophe. This year, the Trump administration and its ally the Chamber of Commerce have infrastructure reform at the top of their agendas, and both the White House and Chamber have released plans on the topic in the recent past. And just like we saw last year with healthcare and taxes, “reform” is code for big-business giveaways that leave American communities, especially low-income communities, out in the cold. Here are three key proposals from the Trump and Chamber plans:

Deregulation and Steamrolling Public Protections

The most predictable proposal present in both the Chamber’s plan and that of the Trump administration is deregulation (they call it “eliminating regulatory barriers”). Both plans argue that deregulation will cut costs without sacrificing quality. There are two problems with this argument. One, unsurprisingly, is that deregulation often compromises both quality and safety. The second problem with deregulation of infrastructure projects is that we would give up the benefits of safeguards while not at all likely to save any of the promised money, either.

In the case of the Trump plan, the most significant deregulatory risk is to the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) which protects species and habitats but also people and communities from polluting projects. And, the Chamber’s infrastructure plan specifically threatens drinking water safety by proposing to roll back the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA’s) ability to veto building permits for projects that negatively impact US waterways, which would increase the risk of water contamination from new highways, dams and pipelines. Its provisions for private leasing of federal lands could also allow pipelines to be built through national parks. Opposing regulation is par for the course for the Chamber of Commerce, which in the past has spoken against the Volks Rule (which strengthens employer obligations to maintain records of workplace injuries and illnesses) as well as other worker-safety regulations like one that protects workers from exposure to high levels of crystalline silica dust on the job. The Chamber even opposes compliance with the Endangered Species Act.

Deregulation will not save money on infrastructure projects because repairing and rebuilding shoddy construction often costs more than simply building it right the first time (sometimes a lot more). Consider a 1960’s construction project in Florida to help control flooding from the Kissimmee River. The original project did not serve its intended purpose, instead becoming stagnant and ultimately polluting the river, killing almost all plants and wildlife in the area. Whereas it cost $194 million in today’s dollars to build it, cleaning up the mess will cost at least $1 billion. That wouldn’t happen today with our current regulatory system for infrastructure projects, that requires robust environmental review.

Not only would steamrolling environmental review rules do unacceptable damage to our environment, these disasters become problems for taxpayers to deal with. Without regulation, communities would be left like those of the Kissimmee River project– faced with a poorly-done project with benefits that never materialize, now consuming more than five times its initial cost simply to reverse the damage it has done. Truly, deregulation would lead to the worst of both worlds.

The Threat of Public-Private Partnerships

Another commonality between the Trump and Chamber plans is a focus on private investment and public-private partnerships. The Trump plan follows the Chamber’s lead by expanding the use of Private Activity Bonds (a key financing tool for public-private partnerships, or “P3s”), allowing privatization of federal infrastructure, and reducing or eliminating constraints to P3s in transit, transportation, provision of water, and even the Veterans Affairs department. The Chamber and the Trump administration claim that these P3s will lead to high-quality services and projects that cost less and give the public more choice, but these claims are erroneous.

First, P3s are not cheaper since private contracts are notorious for their hidden costs. Some of them are to the local government – like when Indiana Governor Mitch Daniels had to pay a private company $447,000 of taxpayer money to offset “losses” from when the governor waived tolls for motorists escaping a massive flood. Some of them are to the public, like when a Chicago consortium operating the city’s parking meters required the city to raise rates in parts of the city by as much as 800% over four years. Private companies typically charge 59% more than public entities to provide utilities like water (in Coatesville, PA the increase was 282% between 2001 and 2015). When a private company began charging tolls on the MLK Freeway in Virginia for the first time in decades, the governor had to step in and renegotiate the deal after some residents received bills totaling more than $10,000. Private companies expect revenue, sometimes an unrealistic amount, and if they don’t get it, they’ll take steps to recover the difference.

The Chamber claims that cities will be able to choose among competing bids, so they can just avoid these bad deals. Well, that may be true in rich areas, but low-income communities won’t be able to offer such lucrative contracts. Some public projects just aren’t profitable on their own. To expect private companies to take a loss in order to help low-income communities is naive. Even if these projects are taken on, expect user fees to be so high that many residents will no longer be able to afford the prices of essential services like water to their homes or the tolls on the roads to their jobs.

This isn’t always true, of course – there are plenty of P3s that do provide services at a discounted cost. Unfortunately, most savings claimed by private contractors are due to huge layoffs and underpayment of wages (specifically, from finding ways to avoid having to pay prevailing wage requirements). That’s what United Water did when they signed a deal to operate Atlanta’s water system in 1999, then proceeded to fire more than half the system’s employees and cut training for the rest. In 2003, the city decided they’d had enough of constant service problems, water-main breaks and even occasional boil-only alerts. They dissolved the partnership.

P3s are supposed to give the public more say, at least – but even this claim is questionable. If the city of Chicago wants to put more bike lanes on its road, they are restricted from making these improvements. Why? Because a private company runs their parking meters, and more people bicycling means fewer paying tolls. The city also has to reimburse the company if they want to close a street (say, for a parade or street fair). The contract went through city council in four days, with no hearings or opportunities for public input. Now, regretful city officials are locked in to the deal. Public-private partnership contracts are also known to contain “non-compete” clauses to protect their profits. That company in Norfolk, VA charging drivers $10,000 in tolls put a clause in their contract limiting the city’s ability to erect or improve “alternative facilities” for drivers who can’t afford such hefty fees. Who exactly has “more say” in these deals? Not the city’s residents.

The bottom line is, the most important thing for a private company isn’t providing high-quality service. It’s not improving the community. It’s not even the well-being of their workers. It’s profit. If other considerations – like safety, pollution, or quality – conflict with profit, expect private corporations to put profit first.

Cutting federal funding

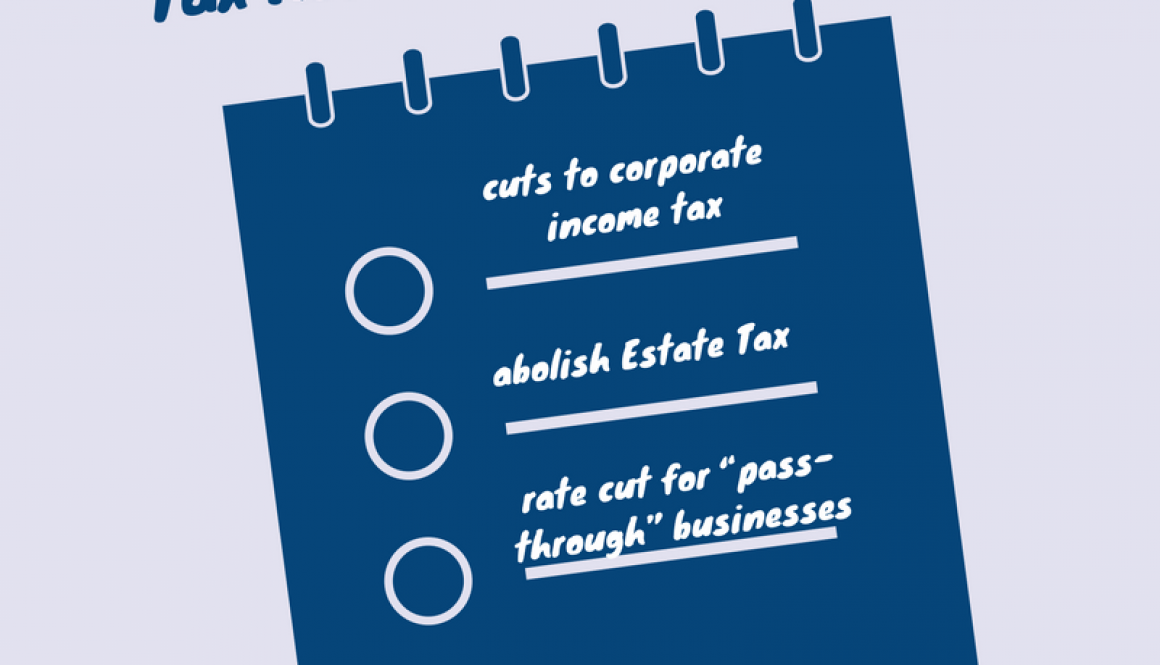

Not only does the Trump administration agree with the Chamber’s mistaken belief that safeguarding public protections isn’t necessary, and that private investment is preferable to public, but they have an additional shared priority for infrastructure reform: they don’t want the federal government to pay for it. The administration’s plan calls for $200 billion in federal investment, but it also calls for $280 billion in cuts to services. That’s a $1.40 loss for every new $1 available, and will lead to massive job losses. State and local governments, used to shouldering 20% of the costs of new infrastructure projects, will now be asked to take on 80%. Worse, under the Incentives Program, even the meager federal funds still available will be preferentially allocated to projects that show strong revenue or revenue potential (i.e. the projects where they are least needed). Some cities will be able to raise the money by increasing state and local taxes, but others will be forced into public-private partnerships to try to make up the difference. Communities too poor to raise revenue through taxation or attract profit-motivated investors face the prospect of simply being unable to afford to fix their broken infrastructure at all. Propaganda from the Trump administration calls this a “$1.5 trillion plan” for infrastructure investment. Don’t be fooled. Most of this money is coming from two places: hypothetical private investors, and taxpayers.

Both the Chamber and the Trump infrastructure plans laud running the government “like a business.” That should alarm you because, to a business, you are nothing more than a revenue-generating customer. But Americans are not the government’s customers. We are its owners. Customers just pay and take what’s available, but owners can demand something better. Stand with Public Citizen and organizations around the country to say: our schools, highways, hospitals, and water are not for sale to the highest bidder. We demand a government that puts people over profits when it comes to infrastructure investments.

Cross-posted on Daily Kos and Citizen Vox.