The Chamber’s Report Claiming Forced Arbitration Benefits Workers is a Farce

Recently, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce-affiliated Institute for Legal Reform (ILR) released a report titled “Fairer, Faster, Better: An Empirical Assessment of Employment Arbitration.” If that title causes you to raise an eyebrow, you’re right to be suspicious. Through dubious evidence and misleading rationale, the ILR report concludes that workers benefit more by being forced into arbitration rather than being allowed to press their claim in open court before a neutral judge and jury.

Forced arbitration is a system wherein workers must give up their right to sue their employer or join a class action against the employer should they face harm such as discrimination or harassment in the workplace. Rather than have these claims of harms assessed by an impartial judge and jury, employees under forced arbitration clauses in their contracts must instead seek to address grievances before private arbitrators. These arbitrators do not have to follow judicial precedent, and the complaints alleged in arbitration cases are rarely made public, keeping other employees or the public at large in the dark about the harms that have occurred within a corporation. For these and other reasons, despite the ILR’s claims, forced arbitration is very much not beneficial to workers.

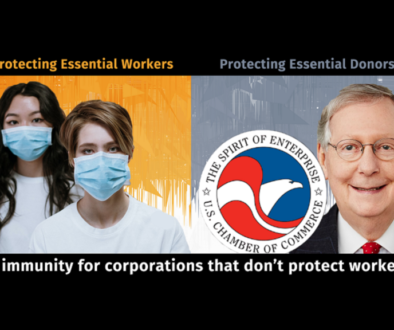

The Chamber and ILR have longed advocated for forced arbitration, a dispute resolution process that advantages Big Business, for example by allowing companies to escape full accountability for wrongdoing like wage theft and misclassification of workers.

The ILR report was written by ndp | analytics, a strategic research firm that for large corporate clients. The report seems designed as a tool for corporate lobbyists to sway lawmakers to oppose any legislation that would prohibit companies from forcing workers, consumers, and small businesses into forced arbitration. It is no surprise, then, that the report was conveniently published shortly before a hearing in the U.S. House of Representatives on forced arbitration.

Over the years, the Chamber has consistently taken anti-worker stances on other matters of civil justice and workplace safety. The ILR report even fits with one of the Chamber’s favorite tricks: claiming that pro-worker policies like overtime protection and a higher minimum wage would be harmful to workers. The Chamber loves to pretend it’s standing up for David when it advocates for Goliath’s favored policies. The Chamber’s stance on forced arbitration flies in the face of the overwhelming consensus among labor experts that the practice is harmful to workers.

The ILR’s so-called “empirical assessment” mentioned in the report’s title amounts to selectively using misleading data to advance an ideological narrative, and the report’s methodology is designed to skew the results in ways that favor the Chamber’s dubious claims.

Labor policy experts Terri Gerstein and Heidi Shierhold write in the American Prospect that the report is “an epic presentation of wrong answers to wrong questions.” Gertstein and Shierholz note that the report’s data is glaringly selective in deeply misleading ways. For instance, the report omits class actions and state court lawsuits in its litigation data, glosses over the fact that forced arbitration’s biggest problem is that it “prevents workers from ever bringing cases in the first place,” and neglects decades of established academic studies on the topic showing that consumers and workers lose out when they are forced into arbitration.

In an expanded critique of the report on the Economic Policy Institute blog, Gertstein and Shierholz note several more flaws in the report’s methods and conclusions. These include that:

- The information available on arbitration is extremely limited and the report analyzes only a small fraction of the arbitration cases that occurred between 2014 and 2018

- The report analyzes employees in the arbitration sample with much higher earnings than the general public

- The report fails to consider the benefit litigation has in securing settlements in cases that do not go to trial

The end result, Gerstein and Shierholz argue, is to skew the results of the analysis toward the Chamber’s pre-existing premise that forced arbitration is beneficial for workers.

Perhaps the Chamber is tossing out every argument it can in the hopes that something will stick, no matter how patently ridiculous the claim, because it sees the growing bipartisan momentum against forced arbitration. Three congressional hearings focusing on forced arbitration have already been held in 2019 alone. In February, Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-CT) and Rep. Hank Johnson (D-GA) introduced the Forced Arbitration Injustice Repeal (FAIR) Act in both the U.S. House of Representatives and U.S. Senate. The FAIR Act would prohibit companies from forcing consumers, workers, and small businesses into using arbitration before a dispute has even occurred. And according to a recent survey, more than 80 percent of both Republicans and Democrats support ending the practice of forcing workers, consumers, and small businesses into arbitration.

Forced arbitration restricts the rights of workers, consumers, and small businesses to seek justice in court before an impartial judge and jury and shields corporations from accountability for illegal practices and other wrongdoing. We should see ILR’s flailing for what it is: an attempt by the Chamber, afraid of the strength of the movement against forced arbitration, to pull the wool over lawmakers’—and the public’s—eyes so it can preserve anti-worker policies that benefit the bottom line of its corporate benefactors.

U.S. Chamber Watch is a project of Public Citizen. If you’d like to learn more about the Chamber, you can always visit us on www.chamberofcommercewatch.org or follow us on Facebook and Twitter.