Then vs Now: Corporate Criticisms of Climate Disclosures are Old News

Written and Submitted by Carly Fabian

Corporations have been making bogeymen out of disclosure requirements for 88 years. The sky hasn’t fallen yet.

In 1934, Joe Kennedy, the first chair of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), defended the new agency in a speech to the Boston Chamber of Commerce. Speaking to the group that had fought tooth and nail against the creation of the SEC, Kennedy reminded the Chamber that industry had a habit of exaggerating the harm of regulation and disclosure requirements: banks had once claimed the Federal Reserve would “destroy”

banking, and railroad tycoons had once claimed that the Interstate Commerce Act would turn railroads into “streaks of rust.”

American corporations and their trade groups need a similar reminder today.

The SEC’s recent proposed rule on climate-related disclosures is an obvious move given the significance of climate-related developments to individual firms and whole markets. Yet, critics have wasted no time in describing the rule as an unconstitutional part of the agenda to “destroy the extractive industries.”

If these criticisms sound both hyperbolic and familiar, it’s because we’ve heard them before. While trade groups like the Chamber of Commerce justify their criticisms by claiming the SEC is deviating from its mission, hyperbolic criticisms of financial disclosure requirements are older than the SEC itself.

When national disclosure requirements were first proposed in 1933 and 1934 after the 1929 stock exchange crash, the proposed requirements were met with opposition from what was described at the time as one of the largest lobby groups in history.

In response to the proposed regulations, the president of the New York Stock Exchange, Richard Whitney, rapidly organized a coalition of corporations to oppose what became the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. Despite the stock market crash wiping out billions of dollars and triggering the Great Depression, Whitney’s coalition didn’t hesitate to deflect the blame, claiming that it was proposed disclosure requirements, not reckless Wall Street gambling, that would “destroy” the American economy.(1)

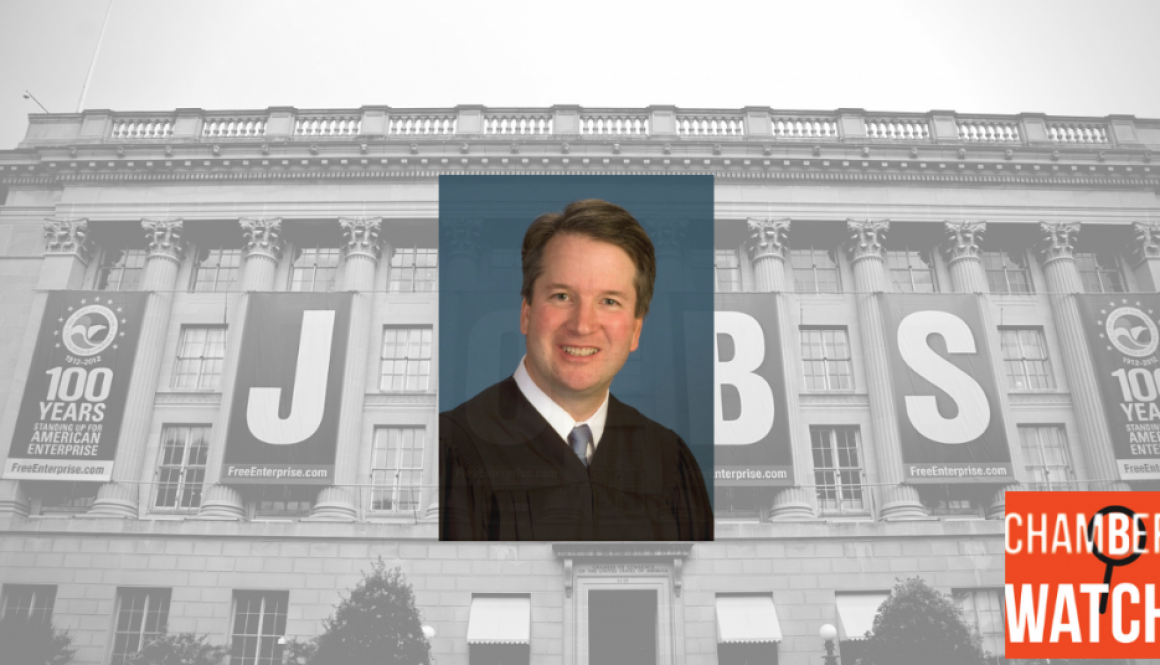

The main players and their criticisms feel familiar today: the Chamber of Commerce claimed the SEC would require a company to “sign away its constitutional rights.” Mining companies claimed it would kill jobs.(2) Oil and petrochemical companies claimed it would produce expensive and useless information for investors.(3)

And the opposition didn’t hold back on hyperbole: banks warned that “nowhere else in the world, nor at any time, has there ever been an attempt made to impose so great a hazard on the conduct of business.”(4) Republicans claimed that the move was designed to “Russianize” industry. “Lenin and Trotsky,” they claimed, “never envisioned such far-reaching possibilities for strangulation.”(5)

Thankfully, these criticisms, some of which could be copied word for word from a modern U.S. Chamber of Commerce press release, were not enough to dissuade FDR and other New Deal advocates for financial regulation. The SEC is now considered essential to the function of capital markets, and even its harshest early critics describe it as the “global gold standard” for financial regulation.

As Public Citizen highlighted in a previous report, this process has repeated itself time and time again. After the collapse of Enron and Worldcom in the early 2000s, the President of the Chamber of Commerce at the time, Tom Donahue claimed that disclosure requirements proposed in the Sarbanes-Oxley Act would “hand American corporations back to the trial lawyers for summary execution.” A few years later, when Donohue was asked about the Sarbanes-Oxley Act he said “Fair enough. A lot of it was well worth doing.”(6)

As criticisms of climate disclosure requirements continue to emerge, grand claims about the SEC’s overreach should be put in the context of 88 years of extreme claims from corporate opponents of sound market rules.

While some companies may be nervous about the prospect of providing climate disclosures, they are increasingly becoming the norm. More than 2,000 companies reviewed by the SEC already disclose some climate-related information, including around 90% of companies in the S&P 500. Moreover, more than 600 of the world’s largest publicly traded companies have made commitments to reach net-zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2050, suggesting that these companies are committing to, at the very least, internally measure their GHG emissions.

Both the proliferation of voluntary climate disclosures and the lessons learned from past disclosure fights suggest that the climate disclosure requirements that are decried as “destructive” today will come to be seen by most of the industry as obvious and necessary tomorrow.

The most strident critics of the SEC climate rule—fossil fuel companies—are exceptions to this rule.

Republicans have warned that if fossil fuel companies are forced to disclose their emissions and climate-related risks, the disclosures will steer capital away from the fossil fuel industry.

If past disclosure fights are any indication, those who doth protest too much may have something to hide: Richard Whitney, the leading opponent of the Securities Exchange Act, turned out to be a financial fraudster and was later convicted of embezzlement. The fossil fuel industry, which has lied for decades to stave off regulatory responses to its lethal business, might be equally right to fear the disinfectant powers of sunlight.

If fossil fuel companies are worried, they should make sure that their supposed climate commitments are reflected internally—and remember the warning of the first SEC Chair: “The Commission will destroy nothing in our business life that is worth preserving.”