U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s Embrace of the Gig Economy Points to Downside for Workers

Last week, a federal judge dismissed a case against a Seattle ordinance that would allow Uber and Lyft drivers to unionize. Seattle’s ordinance was passed in 2015 and would enable drivers to band together and collectively bargain with giant ride-hailing companies regarding pay, benefits, and working conditions.

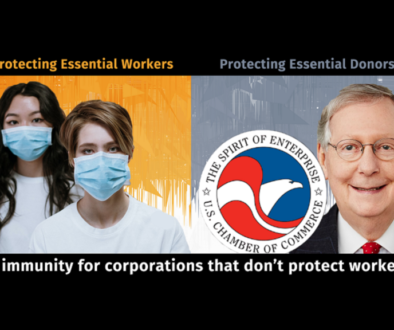

The plaintiff in this case was none other than that relentless defender of corporate exploitation — the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. The Chamber argued without any evidence that the “ordinance will burden innovation, increase prices, and reduce quality and services for consumers.” This is actually the second complaint that the Chamber has filed against this law — an earlier case was thrown out last year — although another suit against the ordinance is still ongoing.

The rights of Uber and Lyft drivers have become an increasingly contentious subject as the ride-hailing platforms have expanded. Although the Seattle ordinance is designed to bypass this issue, much of the debate centers on how to classify these drivers in terms of their relationship with the ride hailing companies for which they work. Uber and Lyft have an incentive to categorize their drivers as “independent contractors”. This enables the companies to dodge monetary obligations — such as payroll taxes for Social Security and Medicare as well as providing health insurance — that come with a traditional employer-employee relationship.

Workers’ rights advocates believe that drivers should be considered employees. After all, prices are set by Uber and Lyft rather than by their “independent” drivers. As employees, drivers would be entitled to overtime pay, workers’ compensation, and other important rights that this status would afford them. In any case, it is easy to see why drivers have voiced concerns about the existing arrangement that deprives them of a host of rights, benefits, and protections.

The current arrangement, under which ride hailing companies treat their drivers as independent contractors with no formal employment contract, has revealed itself to be seriously flawed. Despite Uber’s claims to the contrary, some of its workers fail to make minimum wage. The company is also notorious for its mistreatment of drivers. In fact, a report by the New York Times detailed the types of mind games the company plays in order to get more rides out of its drivers. While Lyft enjoys a far better public reputation, the company still confronts questions over the status of its workers. Allowing Uber and Lyft drivers to unionize could be a solution to many of these problems as it would provide drivers with the bargaining power necessary to successfully negotiate with giant corporations.

The Chamber is predictably opposed to unionizing the ride hailing industry. According to the Chamber, unions are simply relics of the past and the push to represent Uber and Lyft drivers represents a “last gasp” of sorts. The Chamber argues that unionization would limit the freedom of these drivers and that ordinances like the one in Seattle would constitute a violation of the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) and antitrust law. However, in dismissing the case against the ordinance, the district court judge noted that the NLRA does not in fact prevent the city from passing such a lawcovering independent contractors.

The dispute over the Seattle ordinance and the status of Uber and Lyft drivers points to a larger debate about the nature of the “gig economy”. The gig economy — in which people earn money through flexible, short-term arrangements like driving for Uber or performing chores on Task Rabbit — represents a major shift in the workforce over the past few years. While the gig economy has expanded earning opportunities for many, it also poses serious risks for individuals who operate outside of traditional employee contracts. Unions could help to ensure that gig economy workers have access to health plans, higher wages, paid leave and a certain amount of employment stability. While a recent survey revealed that a majority of gig economy workers believe they should have access to greater benefits, the Chamber argues that the gig economy “seems to be working just fine.”

The Chamber’s insistence that everything is going swimmingly with the gig economy should come as no surprise. The gig economy has been a boon to giant corporations by reducing their labor costs, and the Chamber has a consistent record of putting profits before people. The Chamber also has a long history of fighting against workers’ protections, given that it was initially founded “to act as a counterweight to the growing labor movement.” The gig economy’s role in goosing corporate profits while weakening the labor movement explains why the Chamber was so determined to fight the Seattle ordinance in court.

It is often easy to become seduced by the siren song of technological “progress” and “innovation.” The Chamber’s embrace of the gig economy should serve as a warning to us all that simply because an industry is new and “innovative” doesn’t mean that it shouldn’t be scrutinized to see if it treats its workers fairly and justly.